Recently, former Wales captain Sam Warburton blew the long whistle on his career at the tender age of 29. The two time Lions captain and inspirational Welsh back row was so battered, and held together by tape that he decided he couldn’t go on any longer. And who can blame him?

Serious rugby injuries are debilitating. Having suffered a few myself, I can testify to the fact that they are all consuming and massive burden on life off the field for both player and their families.

Joint injuries lead to arthritis and concussions – which are the most common serious injury in rugby at the moment – can cause serious damage not immediately, but in the distant future, well after players have retired and are living a ‘normal’ life.

Ben Smith, one of the world’s best players at the moment, is being kept on ice by All Black coach Steve Hansen as he is one concussion short of his career ending. The All Blacks World Cup bid may just go up in smoke if so. The almost fatal-to-the-cause injury to Dan Carter in 2011 is still fresh in the minds of many of New Zealand’s pessimists. Sudden ends to careers are very much a modern reality.

This may be more palatable when we are talking about double World Cup winners or Lions’ captains. They have presumably made their millions at rich Clubs and with their endorsement contracts. But the game is no less brutal on the ground at every level. France has had its fourth player die from rugby related injuries in their lower leagues. This is unacceptable and there is rapidly building consensus that the game has to change. Modern law changes are trialing the tackle line becoming below the nipples and while this could potentially reduce high collisions it is not an all-encompassing solution.

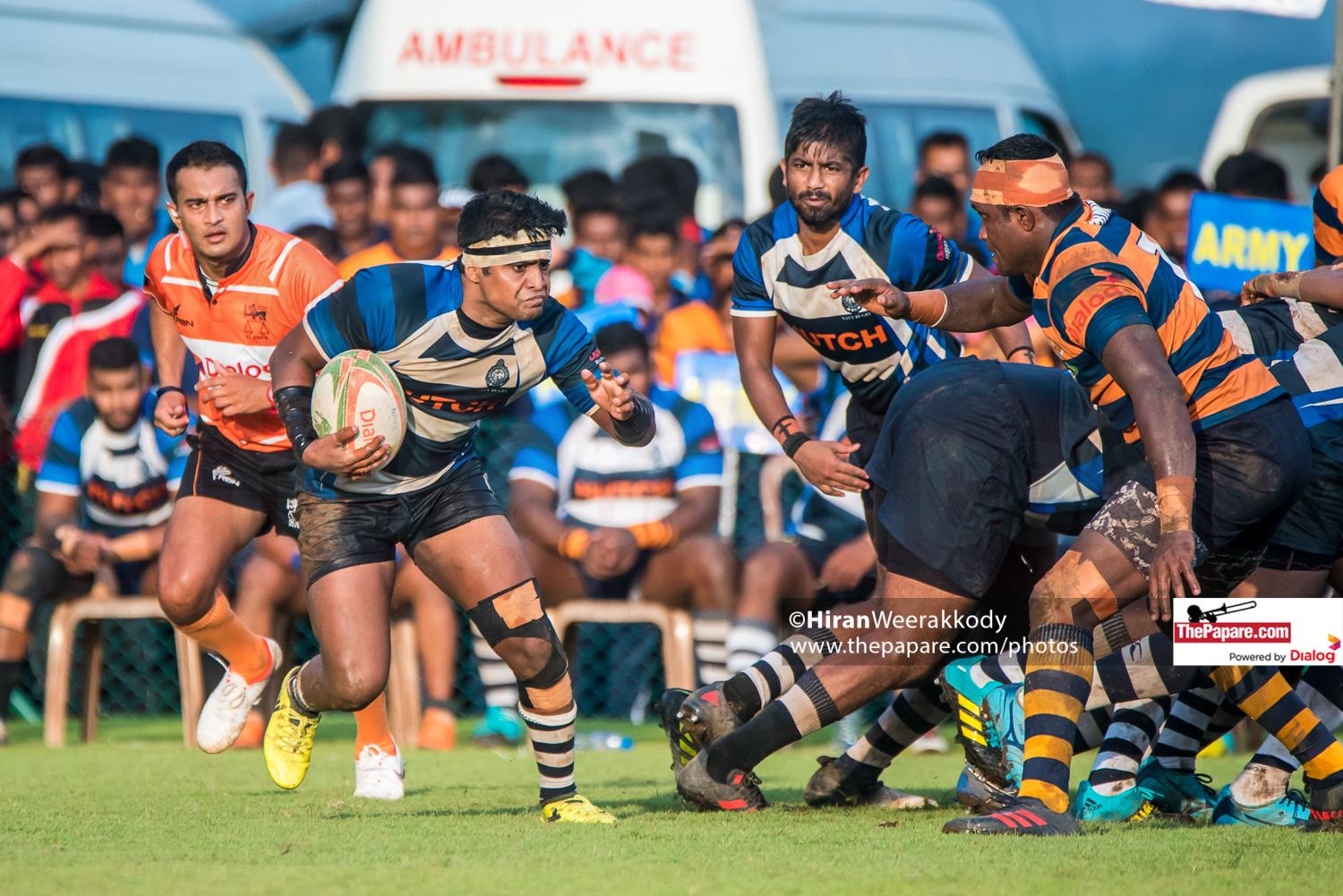

Read More: Has Kandy found a new golden boy?

One of the reasons being, that this year has shown research to the effect that the tackler suffered more injuries in 2018 than the tackled player. This means that tacklers are becoming targets for big ball runners, and at close quarters there’s very little that can be done to ensure tackle techniques against big front five runners, coming in low and hard are injury free. The sheer premium on possession means that tackle techniques have evolved – or perhaps regressed – to ensure that if you can’t win the ball in the collision, you at least slow it down. This has led to tackles getting higher and higher and the safe techniques being abandoned.

Read More: League winning coach to CR & FC

A case in point in Radeesha Seneviratne, the former Police and CR back rower, whose skills at the breakdown are excellent. However, as a result of his impeccable body position he has suffered innumerable concussions from bigger players falling all over him. Too many that I have noticed for him to still be playing rugby. And yet, he plays on. Many kids who have taken obviously heavy head knocks have continued playing in schools games as well.

The way that rugby is played here in Sri Lanka we see players from well-conditioned teams – especially in the lower divisions – coming up against players from teams that do not have a good strength and conditioning regime, mostly in warm up games or knock out tournaments. The fall out is invariably that the weaker team players end up rather worse for wear.

Add to this the quality of grounds that most teams train at, and every tackle which drops the ball carrier to the floor feels like a double hit because of the hard nature of our grounds. Those who have played rugby abroad will appreciate that in most tackles in England or New Zealand or any part of the world that players rugby in winter, you only have to worry about one collision – the one between the ball carrier and the tackler.

In Sri Lanka, many people avoid the damage done to shoulders, knees, hips and heads, when they hit a near concrete floor with a sparse covering of grass in the heat of April. These are matters not discussed, and given that the players graduate from school and may only need their hip replacements or shoulder reconstructions into their thirties and forties, nobody really cares.

Not too long ago, one school had a player that died on the first day of practice while on an ill-advised road run. This season another player suffered a head injury that has left him partially unable to use his limbs. Both players are not from affluent backgrounds, and in the latter case, the family do not even have the mercy of death. Ironically, both these accidents happened in the biggest rugby schools in the country. Hopefully, this will mean that the families received some reparations although no amount of money would suffice.

The Professional Rugby Injury Surveillance Project in England, showed that national and club players were 5 times more likely to get injured in 2017/18 than they were previously with the average lay off of the players rising by more than ten days to a mean of thirty days out with an injury.

These are alarming statistics and despite making allowances for Eddie Jones’ high intensity training, these statistics are likely to be mirrored in our part of the world as well. A part of the world where high costs of x-rays, MRI’s and rehabilitation may lead to injuries lasting longer or becoming more chronic.

The anecdotal evidence of players being injected to allow them to play through an injury pain free, or the number of pain killers the average player pops during a season will make for a staggering compilation here in the local context. Unchecked substance abuse is also a huge problem in Sri Lanka, with regular testing being too prohibitively costly.

As much as I hate to say it, the game we love, is becoming way too dangerous.

While that is the problem of World Rugby to take a lead on, I think it is imperative that the Schools Associations and SLR ensure that all players are adequately insured. This coverage must extend to rehabilitation as well, as otherwise players are cut loose after an obligatory operation and left to fend for themselves.

Surgical intervention is costly, but post care is the most important thing for a player to recover from such an intervention. Lack of proper care, and the players’ knowledge that they are the ultimate losers means that they sometimes shy away from contact especially at international level, which is something that may point to our dropping international standards.

While tournament organisers go to great lengths to obtain security for referees and assurances of crowd control, we may need to start insisting on seeing full-time medical staff and insurance contracts as prerequisites for tournament entry. Lack of such measures, will affect not only the quality of the game, but certainly the quality of players’ lives.

Shanaka Amarasinghe writes an entertaining blog. Find it here