This week we started shooting for season three of our popular segment ‘Legends’ and we had the opportunity to talk to two former players who changed some popular cricketing myths – Brendon Kuruppu and Ashantha De Mel. The lesson both in cricket and life is that unless you believe in yourself and try to make a difference, you will continue to believe in myths, unable to realize your full potential.

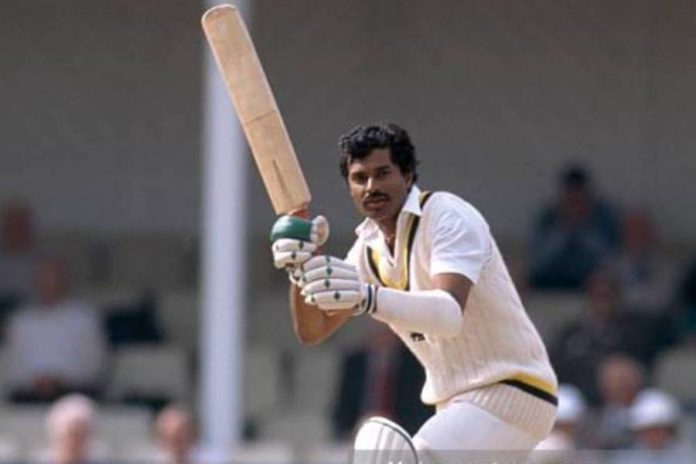

Kuruppu was a dashing opening batsman. Strangely, there was this notion that his game was more suited for limited overs cricket. Hence, he made his ODI debut in 1983 and had to wait four more years before winning his Test cap.

Read – Are we Sri Lankans scared of sports psychologists?

Four years is a long wait and obviously creates doubts in your mind. You tend to believe that the world is right and give up on your own aspirations. Often what happens is that you tend to fine tune your skills in the particular discipline you are said to be good at; in Brendon’s case, one-dayers.

But finally when an opportunity came his way, Brendon seized it from both hands. The Kiwis were in town and he was handed his Test cap for the opening Test at the Colombo Cricket Club grounds. This was sink or swim for Brendon. New Zealand were no pushovers and were spearheaded by a certain Sir Richard Hadlee.

Brendon didn’t just survive and secure his place for the next Test but went onto create a series of new records, he became the first Sri Lankan to score a double hundred in Test cricket.

At that time only two others had achieved the feat of scoring a double hundreds on debut – Tip Foster of England and Lawrence Rowe of West Indies. Since Brendon, two others have joined the elite list – Jacques Rudolph of South Africa and Mathew Sinclair of New Zealand.

Brendon batted for 777 minutes, in other words, he occupied the crease for more than 12 hours. Andrew Flintoff’s legendary remark after winning his first Man of the Match award having been repeatedly heckled by British press for being overweight was ‘Not bad for a fat lad’. Brendon would have said, ‘Not bad for a slogger.’

What is remarkable is that to date it remains the slowest double hundred in the history of the game. Application, commitment, patience and perseverance – Brendon had it all. Not only that, Brendon is the only player in Test cricket to have been on the field on all five days. Duleep Mendis declared soon after Brendon reached the double hundred and then he had to keep wickets for the next two and half days as the Kiwis replied with 406 for five in their first innings. The game was a high scoring draw.

Sadly, a couple of hours after the game, the Kiwis were packing their bags and heading home as the tour was abandoned after the Central Bus Station bomb blast in Pettah.

Sri Lanka was alienated by rest of the cricketing world as the war was on and Brendon played just four Test matches.

Read Also – When Murali took cricket to Jaffna

Like Brendon, De Mel had his moments of all places at the MCG. Sri Lanka were pushovers in the 1980s and De Mel cracking Richie Richardson’s jaw with a bouncer was a sight to behold. Rumesh Ratnayake from the other end was turning up the heat sending Larry Gomes to hospital and hitting Clive Lloyd. It was the West Indies fast bowlers who were creating fear in batsmen those days and here were two rookie Sri Lankans who put the West Indies on the back foot. The message was loud and clear. Sri Lankans also could bowl fast.

Several years later, De Mel as a selector was involved in several major decisions that shaped the future of Sri Lankan cricket.

The foremost of them is relieving Kumar Sangakkara of wicket keeping duties in Test match cricket. Twenty years ago, the trend was for teams to rely heavily on wicketkeepers who could bat rather than pure wicketkeepers. Hence, Geraint Jones was preferred over Chris Read in England while Moin Khan had an edge over Rashid Latif. In South Africa, Gerhardus Liebenberg was the better wicketkeeper but Mark Boucher was the better batsman and hence the latter had got the nod ahead of the former.

De Mel was swimming against the tide. He took a rather unpopular decision at that time. Sanga resisted initially saying that keeping wickets enabled him to see the ball better. De Mel then threw down the gauntlet saying that if he intended to keep wickets, he had to bat at number seven – like Adam Gilchrist. Sanga then took a backward step and the rest is history. He averaged 66 as a specialist batsman, way above his career average of 57.