Much has changed in South Africa these days. The end of apartheid has brought about equal opportunities to all South Africans. Jeryl Woutersz, the Sri Lankan team manager would vouch for the change. He was one of the first Sri Lankans to play cricket in South Africa having joined the rebel tour in 1982.

Rex Clementine in Port Elizabeth

Thanks to Gamini Dissanayake’s promise to the International Cricket Council that he will fix the infrastructure in the country to play Test cricket, Sri Lanka was granted full membership of the ICC. Having got the green light, Dissanayake went about things enthusiastically upgrading the venues. He had hired, of all people, Sir Gary Sobers to be the coach of the national cricket team.

Then he was shaken up. Exactly six months after the country had played the inaugural Test match, Dissanayake got to know that a group of Sri Lankans were planning to go on a rebel tour to South Africa.

Those days South Africa had been isolated by the world due to the country’s apartheid policies that saw racial segregation. Nelson Mandela was still in prison and most democratic nations wanted to do little with South Africa.

Colin Rushmere, who lived right here in Port Elizabeth was a lawyer by profession; He died last year. It was he who made the trip to Colombo from Port Elizabeth via Johannesburg and Hong Kong for negotiations with Sri Lankan players. He had brought along with him 14 contracts to be signed by the players.

Prior to this, Dr. Ali Bacher, former Test captain and by then, the boss of the South Africa cricket board, made a stop during his trip to London to speak to member boards in the sidelines of the ICC meeting. He also made a quick trip to Holland to meet Tony Opatha, the mastermind of the tour, who had initially asked for US$ 30,000 for each player.

“You think we have that much of cash? You must be in the cuckoo land,” Bacher had told Opatha and eventually, the parties had settled down for a lower rate.

The eventual pulling out of the team’s two premier batsmen, Duleep Mendis and Roy Dias, hurt the players’ case.

Dissanayake was putting his full might to kill the tour and had entrusted his Vice-President Raja Mahendran, the business tycoon, who had employed several players at Maharaja’s to talk the players out of the tour.

Duleep Mendis was one of the employees at Maharaja’s. Initially, Mendis was adamant on going on the tour. Raja Mahendran, a generous man, who had done much for the development of the game didn’t want to see Sri Lanka cricket suffer with the departure of the cream of the players. So, he got tough on Mendis.

“Not only will I stop employing you, I will make sure that no one else in the country employs you,” he told Mendis. Under pressure, the batsman gave in and with him followed Dias.

The South African Breweries sponsored Sri Lanka’s tour. The First-Class structure in the South Africa – Currie Cup – was quite strong and the tourists struggled to compete against a quality opposition.

Of the 12 games they played, Sri Lanka managed to draw two and went on to lose the rest of them. Their bowling lacked penetration, and the team had to depend heavily on Lalith Kaluperuma.

The Sri Lankan Board, taking a cue out of the books of England and Australia, wanted to hand the players a ban of five years. But Dissanayake would have none of it. He did one better and banned them for 25 years.

The statement he issued to the press summed up his mindset. “The lepers who are surreptitiously worming their way to South Africa must understand that they are not playing fair by the coloured world,” he said.

The ban meant that the players were not allowed to have any association with the sport. There was very little support for them from the society as well.

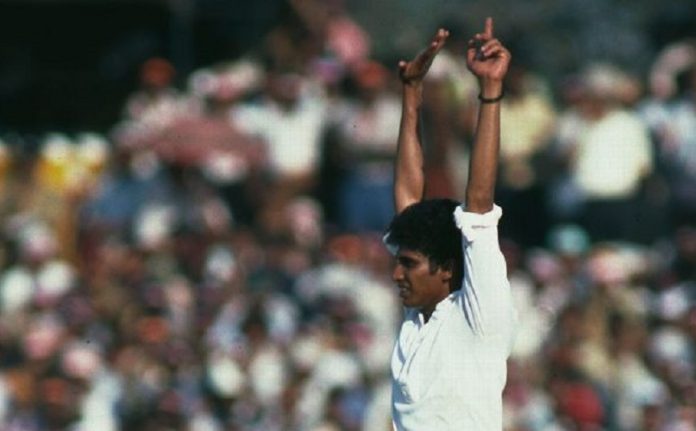

Of all people, captain Bandula Warnapura suffered the most. A genuine man who called a spade a spade, he had little to do in putting the tour together. But being the captain, he had to take the bulk of the blame.

His Nalanda College colleague, Anura Ranasingha, suffered from depression and tragically died aged 42.

In 1991, following the release of Mandela from prison, apartheid collapsed. South Africa were readmitted to the ICC. The Sri Lankan authorities then softened the stance ending the bans of players. Many of them returned to the sport in some capacity.

Warnapura held several key positions at SLC. The likes of Hemantha Devapriya took up coaching while Kaluperuma and Mahesh Gunathilaka served as selectors.